Radiocarbon – the way to tell time in the carbon cycle

Radiocarbon (14C) is the radioactive isotope of carbon, with 6 protons and 8 neutrons.

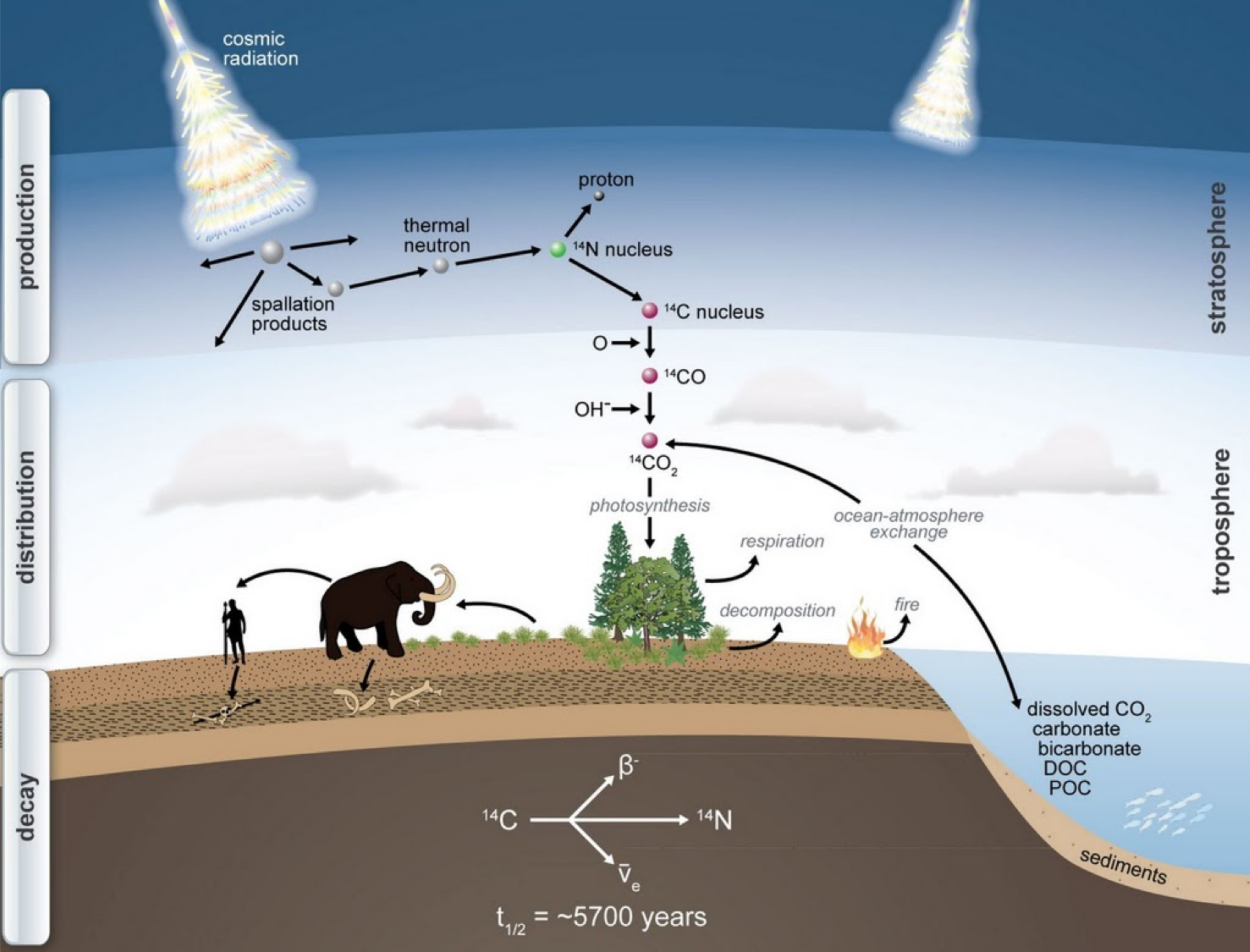

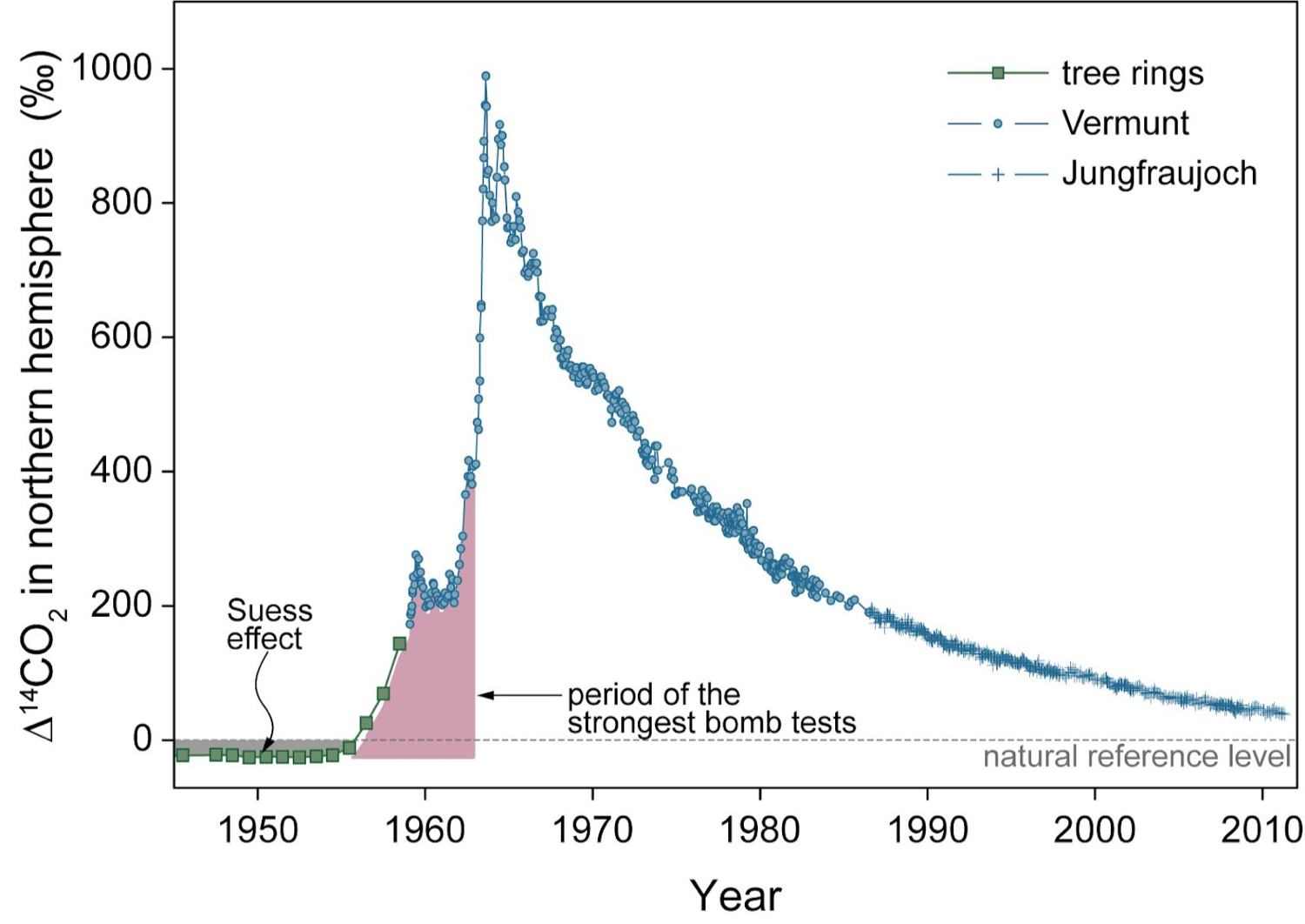

Radiocarbon is produced in three ways: (1) Cosmic-ray generated neutrons interacting with 14N in the atmosphere (see Figure 1) (2) Cosmic-ray interactions with surface minerals (in situ production, generally quite small compared to (1)) (3) Neutrons from thermonuclear reactions interacting with 14N Atmospheric thermonuclear weapons testing in the early 1960’s approximately doubled the amount of 14C in atmospheric CO2 (see Figure 2) Small amounts of 14C are also released by some nuclear reactors, these can be minor but if you are near one you should be aware!

Figure 1: Production of radiocarbon in the upper atmosphere by high energy cosmic rays interacting with O and N atoms. The resulting energetic particle collision can create a 14C nucleus (6 protons and 8 neutrons) from a 14N nucleus (7 protons and 7 neutrons). The 14C atom is quickly oxidized to carbon monoxide and then to carbon dioxide - thus 14C enters the global carbon cycle from the atmosphere. (Schuur et al. 2016).

Figure 1: Production of radiocarbon in the upper atmosphere by high energy cosmic rays interacting with O and N atoms. The resulting energetic particle collision can create a 14C nucleus (6 protons and 8 neutrons) from a 14N nucleus (7 protons and 7 neutrons). The 14C atom is quickly oxidized to carbon monoxide and then to carbon dioxide - thus 14C enters the global carbon cycle from the atmosphere. (Schuur et al. 2016).

Figure 2: ‘Bomb” radiocarbon is the production of 14C by atomic weapons testing in the atmosphere

Figure 2: ‘Bomb” radiocarbon is the production of 14C by atomic weapons testing in the atmosphere

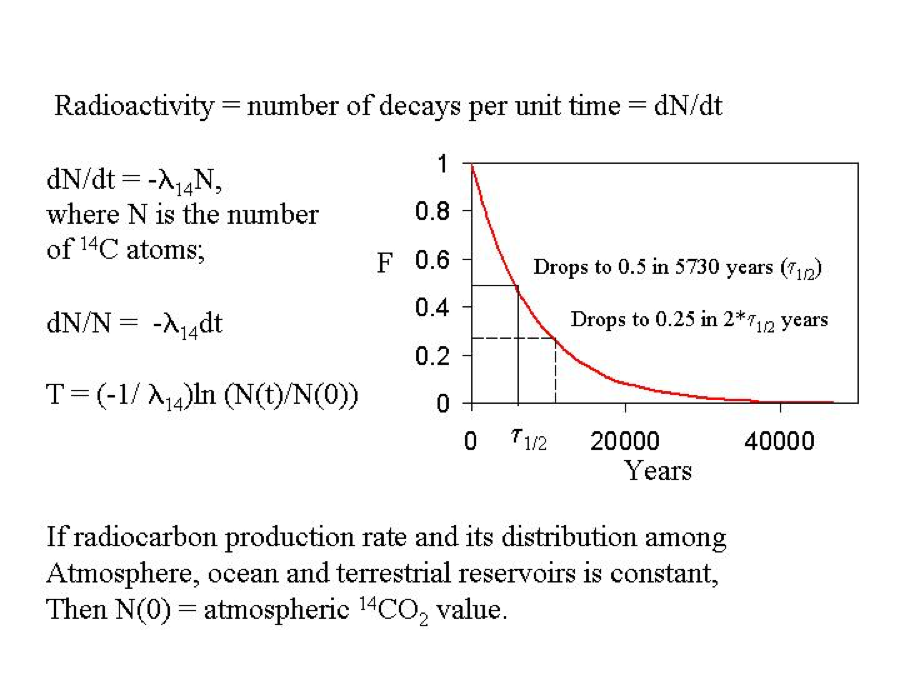

Radiocarbon is destroyed in only one way: Radioactive decay. The combination of 6 protons and 8 neutrons is inherently unstable, and will spontaneously emit an electron from its nucleus. However, this is a rather slow process: the half-life of radiocarbon - the time that it takes for half of the original radiocarbon atoms to revert to 14N is 5730 years. (see Figure 3 for more on half-life)

The balance of production and decay are such that the natural abundance of 14C is roughly one in every trillion (1012) carbon atoms.

Radiocarbon is used to study the carbon cycle in several ways:

1) As a dating tool – to get the ages and accumulation rates of sediments, tropical trees, volcanic eruptions, etc. 2) As a source tracer – for example, comparing the isotopic values of respired CO2 with those of potential substrates will determine which substrate contributes the most;. 3) As an indicator of the rate of exchange of carbon in various reservoirs with atmospheric CO2. 3) As a purposeful tracer (e.g. when 14C is added to a system and traced through it)

Radiocarbon dating

** Telling time with cosmogenic radiocarbon - hundreds of years to ~60,000 years **

The basis of radiocarbon dating is shown in Figure 3. There are a number of assumptions behind this approach.

(1) We assume that the carbon in the object being dated (for example, a plant seed) is derived from a reservoir of carbon (atmospheric CO2 or ocean surface dissolved inorganic C) with a known amount of 14C (this is N0 in Figure 3).

(2) We assume that the carbon in our object remains ‘closed’ to exchange with newer carbon since it formed.

(3) In Figure 3, we are assuming that N0 does not change with time

(4) We assume we know the half-life of radiocarbon.

Figure 3: The basis for radiocarbon dating.

Figure 3: The basis for radiocarbon dating.

We know that the 14C activity of atmospheric CO2 has changed in the past - and this affects the usefulness of 14C to determine the absolute age of an object. Causes of these variations are (1) changes in the earth’s magnetic field (which determines the trajectory of cosmic ray particles hitting the upper atmosphere); (2) changes in the solar output (we can see changes coincident with solar cycles such as the 11-year sunspot cycle) (3) changes in the carbon cycle (the partitioning of carbon among atmosphere, ocean and land).

To determine the 14C content of the atmosphere in the past, we need to measure the 14C in something of known age. The radiocarbon community uses tree rings (or corals dated with an independent method like U/Th) to accomplish this. This tree ring record is used to determine the “Calibrated” age from a radiocarbon measurement. The calibration curves are based on data from several laboratories and there are several programs available over the web that can be used for conversion. Tree ring records go back only to about ~10,000 years. For the latest calibration curves and programs, see the Radiocarbon web site:

Telling time with bomb radiocarbon - years to decades

Further in-depth resources

Schuur, EAG, Druffel, ERM and Trumbore, S. 2016. Radiocarbon and Climate Change: Mechanisms, Applications and Laboratory Techniques. Springer

Torn, M.S., C.W. Swanston, C. Castanha, S.E. Trumbore. 2009. Storage and turnover of natural organic matter in soil. In: IUPAC Series on Biophysico-chemical Processes in Environmental Systems; Volume 2- Biophysico-chemical processes involving natural nonliving organic matter in environmental systems. Series Editors: P. M. Huang and N. Senesi. N., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, USA

Trumbore, S. E. (2009). Radiocarbon and Soil Carbon Dynamics. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 37, 47-66. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.36.031207.124300.