The State of Science: Earth System Modeling

Global climate change has become a critical planetary issue for this century. Aspects of this change are well understood. For example, climate change is caused by human activities that increase the amount greenhouse gases into the Earth’s atmosphere. This results in warming temperatures (including heat waves), sea level rise, and changes in precipitation patterns (including both drought and more intense storms). Increasing temperatures not only affect the planet’s atmosphere, but also the terrestrial processes, both above and below ground. The long-term effects of climate change and elevated concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere on terrestrial ecosystems are less well understood. One of the most important processes affected in terrestrial ecosystems is the soil carbon cycle.

Interactions between the atmosphere, plants, soil and water are built into models designed to understand interactions between Earth’s operating systems. These Earth system models, or ESMs, are important for projecting the future effects of climate change on terrestrial ecosystems, including soil carbon stocks. Given the use of best land management practices, current ESMs predict that there is significant potential for soil to take up a large amount of carbon from the atmosphere within this century – potentially offsetting some greenhouse gas emissions.

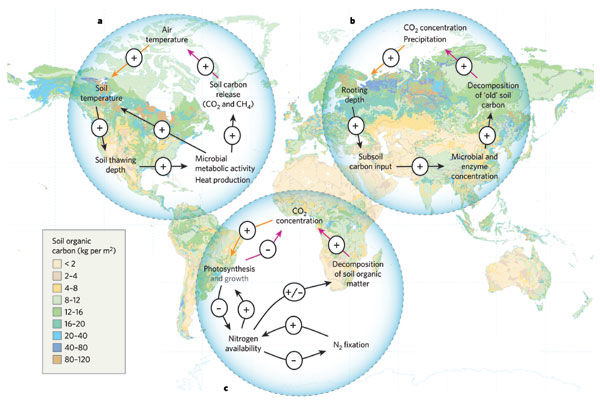

Heimann and Reichstein (2008) suggest that the relationship between climate and carbon in terrestrial systems is actually a series of nested systems of positive feedback loops. Positive feedback loops are systems that as more changes occur the to the drivers of the system, the system is thrown more and more off equilibrium. An example of a smaller nested system within the large global system is how permafrost in Arctic soils is melting due to the increase in global temperate from enhanced greenhouse gas inputs. When the permafrost melts it releases the C trapped within the soil which then oxidizes to form CO2, this then increases the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and accelerates the global temperature rise. Accurately accounting for the nested systems within the larger system creates major challenges in accurate ESMs (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Three examples of positive feedback loops of carbon dioxide with terrestrial ecosystems overlaid on a global map of soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks. (Heimann and Reichmann, 2008).

Figure 1: Three examples of positive feedback loops of carbon dioxide with terrestrial ecosystems overlaid on a global map of soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks. (Heimann and Reichmann, 2008).

Further in-depth resources

Todd-Brown et al. 2014 doi; Heimann and Reichstein (2008) doi

Changing climate and soil carbon: A complicated relationship

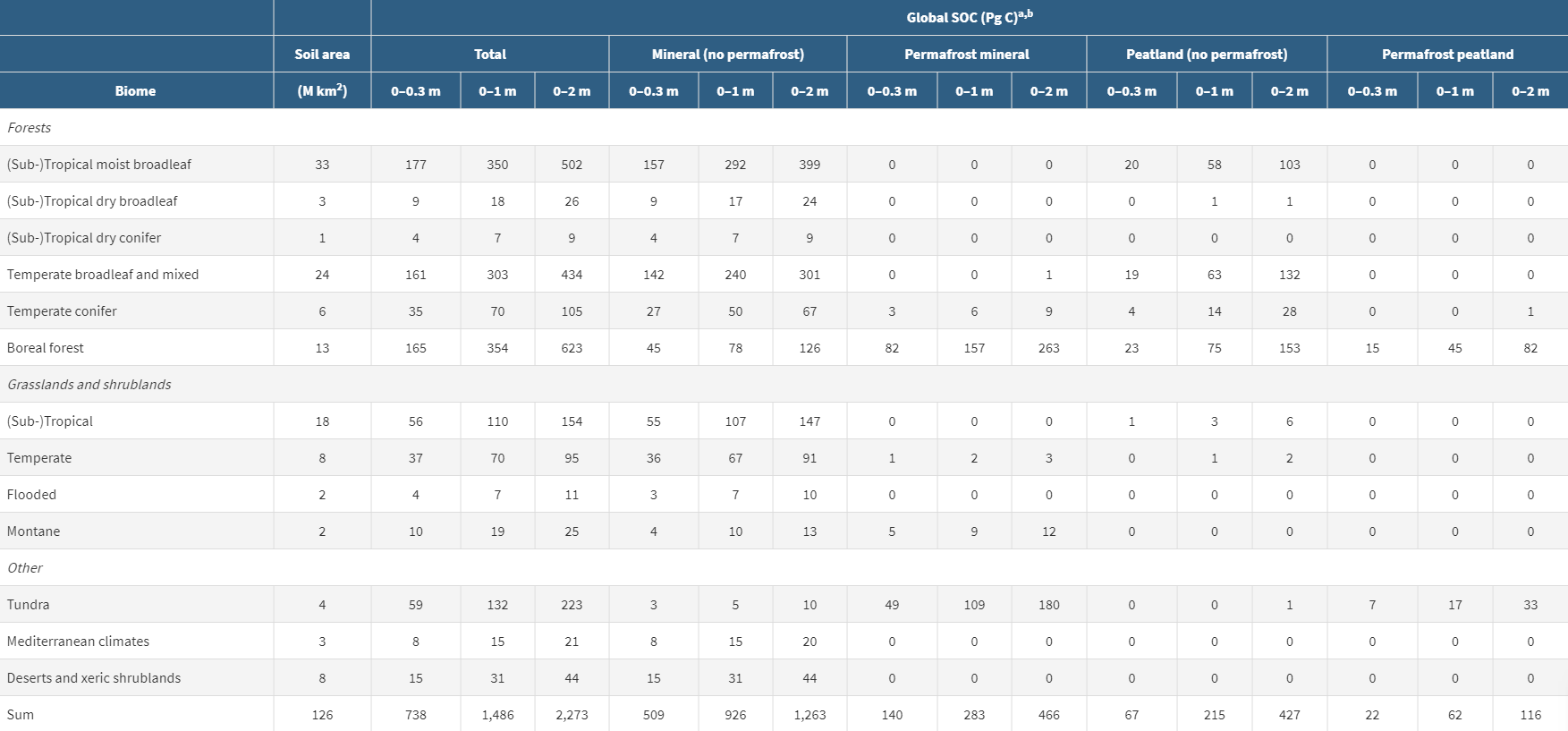

Using ESMs to predict soil carbon proves to be challenging because of the variability that exists within soils. Soils vary based off many factors like parent material, climate, organism, time and topography; therefore, there is difficulty in accounting for all these differences within a global model. Table 1 shows the amount of carbon in each soil by biome. Permafrost and peatlands have some of the highest amounts of organic carbon stored within their soils. As the Earth’s temperature increases, the stored carbon is threatened by the melting of these partially frozen soils and therefore reigniting the metabolisms of the microbes in the soil, which then respire CO2 back into the atmosphere. This melting permafrost is a key example of the uncertainties in the global carbon cycle. Multiple sources of uncertainties lead to variation in carbon cycle projections among models.

Uncertainties in model parameters result from incomplete understanding in how soil carbon decomposition occurs in a variety of ecosystems and soil environments. Uncertainties in model structures occur because of how best to translate our understanding of soil processes into numerical equations across diverse landscapes. Uncertainties in model inputs (including local climate conditions), also contribute to uncertainties in model state. Examples of these uncertainties result in variation among models in the simulated rates of net primary productivity (NPP), soil respiration, land use and land cover change, and the turnover time of live carbon or live plant biomass. Together these uncertainties generate large variation in the projections of soil carbon stocks, fluxes, and their response to environmental change.

Table 1: SOC by biome given by Jackson et al. 2017

Table 1: SOC by biome given by Jackson et al. 2017

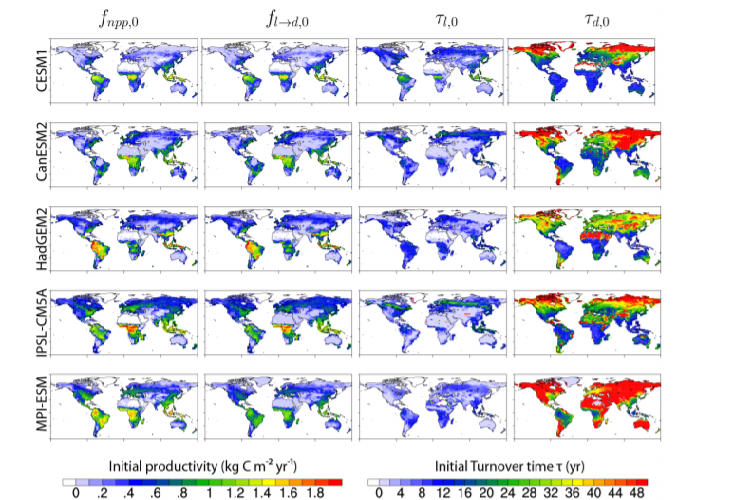

One effort to reduce uncertainty in model predictions is targeting how model structural representations of carbon turnover influence the projections from the Coupled Model Intercomparsion Project Phase 5 (CMIP5; Koven et al. 2015). This paper looks at the two main categories carbon that are considered by models, including live (vegetation) and dead (decomposing organic matter) carbon pools and how they may respond to climate change. By separating the carbon into two separate pools the variables on carbon feedbacks can be better controlled and manipulated within the model. Along with this however there can be uncertainty in the model structure (number of pools) and the model predictions, therefore it is important to accurately represent both pools. Figure 2 shows the results from the CMIP5 model.

Figure 2: The five ESMs once CMIP5 protocol of the two carbon pool system is applied. The left two columns are the carbon inputs (live pools) and the right two columns are the carbon outputs (dead pools) (Koven et al., 2015).

Figure 2: The five ESMs once CMIP5 protocol of the two carbon pool system is applied. The left two columns are the carbon inputs (live pools) and the right two columns are the carbon outputs (dead pools) (Koven et al., 2015).

Further in-depth resources

Olson et al. (2011), doi ; Fung et al., (2005) doi ; Jones et al., 2003 doi ; Friedlingstein et al., (2006) doi ; Friend et al., (2014) doi ; Koven et al. (2015) doi ; Koven et al. (2017) doi

Models for Management: How ESMs help make informed decisions

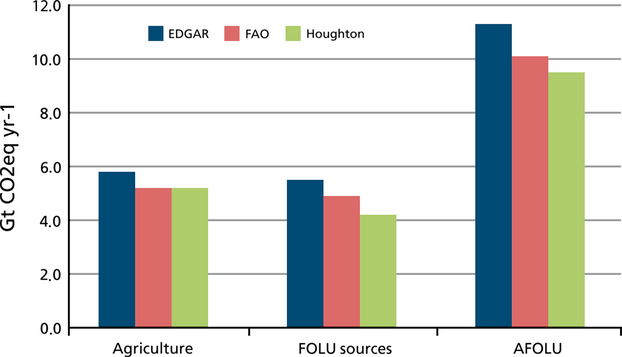

It is important to understand the amount of soil carbon across the globe as well as how it may change through time to manage it correctly. By understanding how soil carbon responds to different management practices we can help manage the land for its best use and for the health of the overall environment. Land use change accounts for 25% of the total anthropogenically sourced greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere. Of this 25%, the biggest contributors are agriculture and deforestation, making them the two main focuses of many ESMs.

Figure 3: The total yearly contribution of CO2 from agriculture, forestry and other land uses (FOLU) and the combined agriculture forestry and other land uses (AFOLU) (Tubiello et al., 2015)

Figure 3: The total yearly contribution of CO2 from agriculture, forestry and other land uses (FOLU) and the combined agriculture forestry and other land uses (AFOLU) (Tubiello et al., 2015)

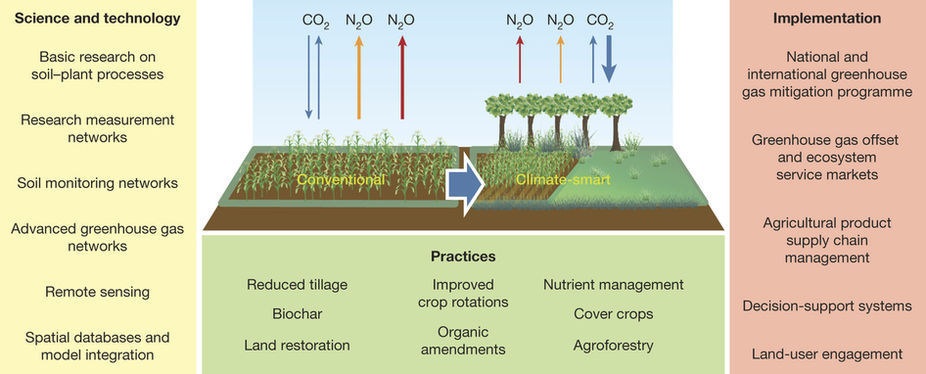

Actions are already being made to help sequester carbon through better land management, specifically in agriculture. The “4 per mil initiative” in France is looking to secure food and climate security by increasing the quantity of organic matter in the top 30-40cm of soils by 4% each year on over 570 million farms across the world 4 permil. Organic matter is the primary component of SOC and there is a strong positive linear correlation between soil organic matter (SOC) and SOC (Bianchi et al., 2008). These movements however are only possible with an integrated implementation approach spanning stake holders, including scientists, land managers, farmers and policy makers. This discussion starts with ESMs estimates of SOC stocks across the globe and then predicting the positive effects that proper land management can have on increasing the SOC in vulnerable areas like those under agriculture. Modeling is part of the discussion but there are multiple components needed to mitigate the loss of soil C. The other components of SOC management include, field testing and monitoring of SOC across sites, coordination with farmers to ensure the management practices are feasible for their operation and implementation through legislation and regulation. The models can be used to guide the process at multiple levels, but they are never the only tool.

Figure 4: Cross discipline cooperation in model creation and implementation of practice and policies to transition into “climate smart” agriculture. (Paustian et al., 2016).

Figure 4: Cross discipline cooperation in model creation and implementation of practice and policies to transition into “climate smart” agriculture. (Paustian et al., 2016).

Further in-depth resources

Tubiello et al., (2015) doi ; Paustian et al.(2016) doi ; Bianchi et al. , 2008 doi

Where have we come from? The first global SOC models

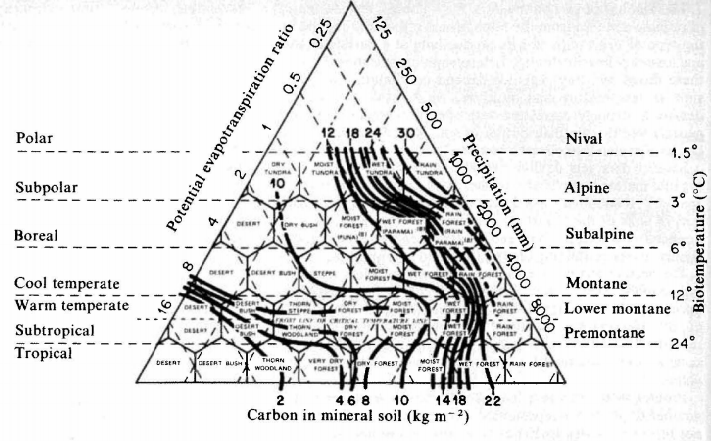

Figure 5 shows one of the first applications of the relationships between soil carbon stocks and broader climate factors, including precipitation, evapotranspiration, and ecotones or biomes (i.e., the Holdridge world life zones). These relationships, however, fail to predict the uncertain effects of climate and land use change.

Figure 5: Contours of soil carbon content overlaid on the Holdridge world life zones, displaying the old view of how carbon stocks were distributed globally (Post et al.1982).

Figure 5: Contours of soil carbon content overlaid on the Holdridge world life zones, displaying the old view of how carbon stocks were distributed globally (Post et al.1982).

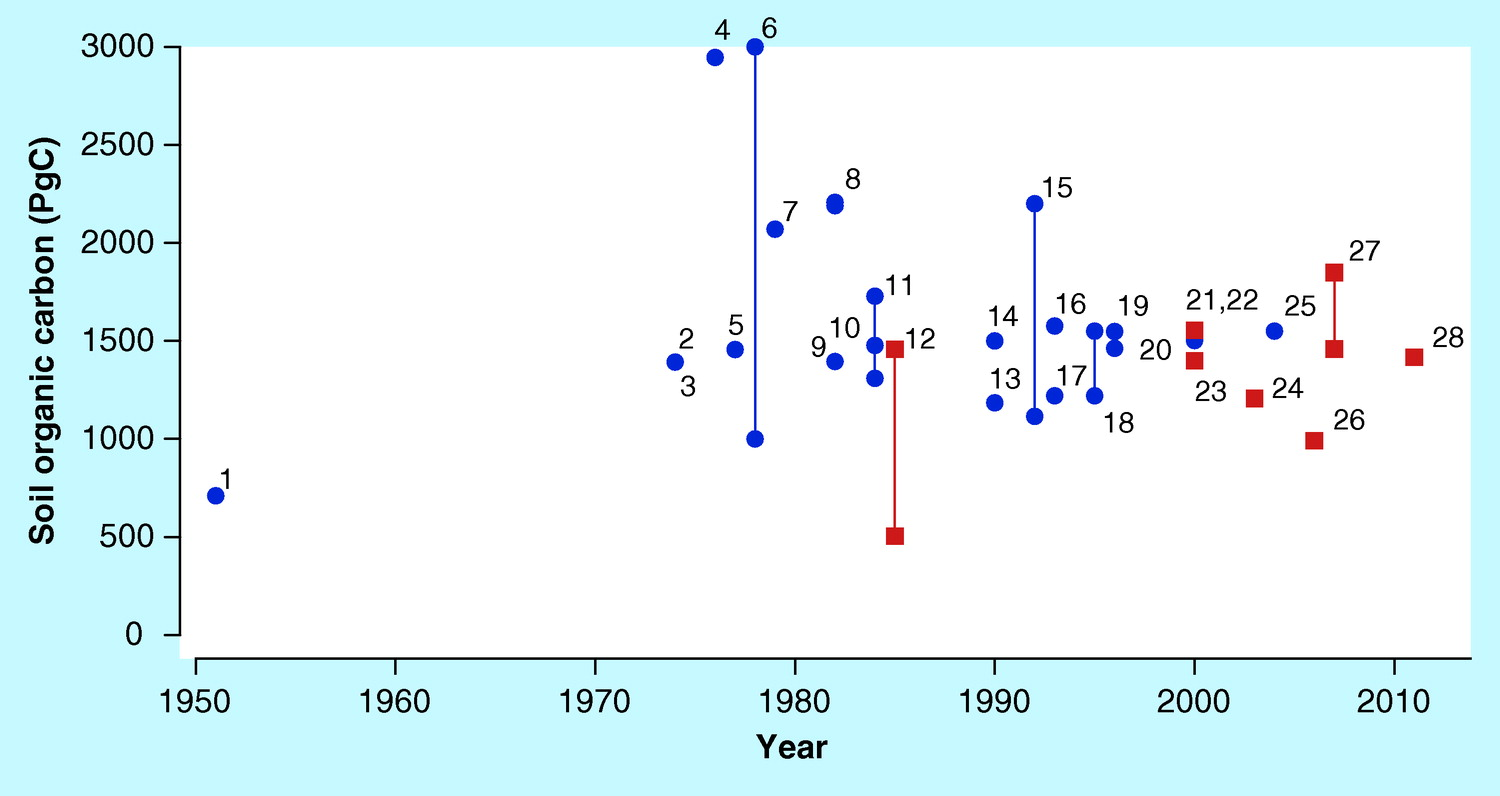

From Figure 5 we have traveled a long way. SOC stocks were initial understood by evapotranspiration rates and precipitation zones, that delineated SOC stocks by biome. It is now understood that SOC has a more complex relationship, dependent on mechanistic relationships between SOC and soil type as well as biomes. Figure 6 shows how the total global estimates in carbon content have evolved overtime. Some estimates have been over the current level (#28) and others have been underestimated. As climate change continues unabated and along with the heavy uncertainty around the relationship of terrestrial carbon and the atmosphere, we need to evolve the ESM models to encompass this change. The modeling community needs to come together to address the uncertainties that arise with the rapid evolution of climate change by basing more off mechanistic science of the relationships driving these changes.

Figure 6: The estimates of the global distribution of carbon density (PgC) extracted from literature of that time with the most recent and agreed upon estimate being #28. Blue color points indicate estimates acquired through non-spatially explicit methods, while red indicates estimates acquired through spatially explicit methods.(Scharlemann et al. 2014).)

Figure 6: The estimates of the global distribution of carbon density (PgC) extracted from literature of that time with the most recent and agreed upon estimate being #28. Blue color points indicate estimates acquired through non-spatially explicit methods, while red indicates estimates acquired through spatially explicit methods.(Scharlemann et al. 2014).)

Further in-depth resources

Post et al., (1982) doi ; Scharlemann et al., (2014) doi

Where are we going? The future of ESMs for SOC stocks through mechanistic modeling

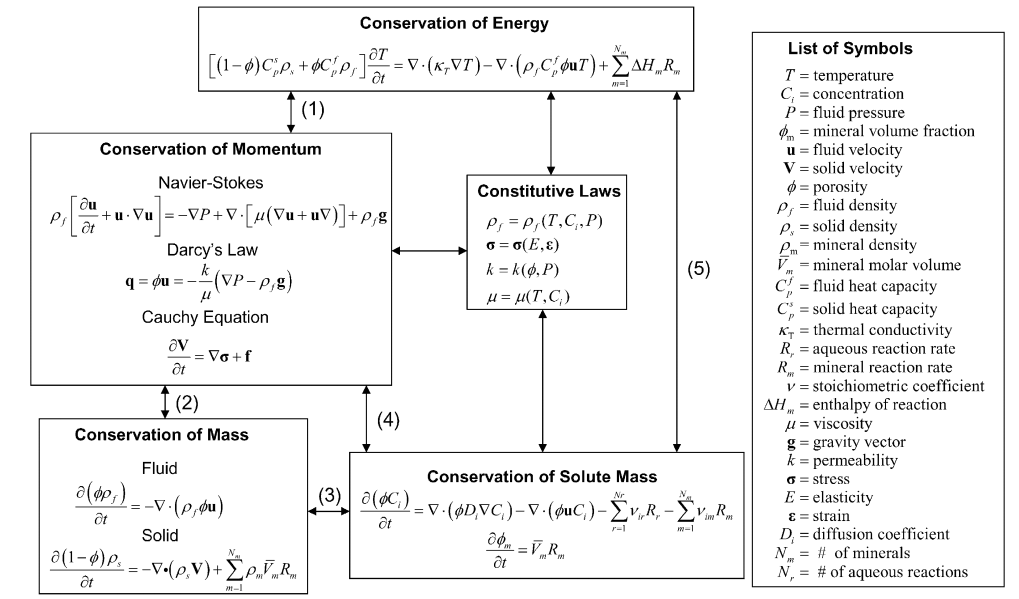

There are several different types of models that have been developed in ESM. Most often the type of model developed depends on the accessibility to the data you have. Empirical models based off statistical relationships from real dataset may not reflect changing conditions brought by climate change. Mechanistic models, on the other hand, are based on how we think a system works. You still need data and arguably more of it but the focus of the model is in the mechanisms that are driving the destabilization of SOC stocks. The benefit is that these models, in theory, should be better able to predict change Steefel et al. (2005) argues taking a more integrated systems approach to ESM development. They describe this scientific integrated system as a model “where individual time and space-dependent processes are linked and where the relative importance of individual sub-processes cannot be fully assessed without considering them in the context of the other dynamic processes”. This means linking all processes of carbon sequestration, organic matter decomposition, and carbon transport across spatial and temporal timescales into a continuum, rather than a separate, linear model.

Figure 7: Examples of governing equations that could be used for a mechanistic modeling of a system (Steefel et al., 2005)

Figure 7: Examples of governing equations that could be used for a mechanistic modeling of a system (Steefel et al., 2005)

For all these approaches there are many challenges to scaling. When a model scales from a soil pore to global scales there are many associated uncertainties. The on the ground data used to validate the model may not represent the true values within the system and the data could upscale or downscale the model predictions. Also, there may there is not enough data for the model and extrapolating it to cover an ecosystem or entire planet is not representative of the randomness within the system. Nonetheless, changing from a linear model to a multi continua model is the new focus of ESMs in order to create accurate forecasts for how climate change may affect carbon stocks across different ecosystems. The mechanisms of carbon sequestration and decomposition are so complex and variant by climate that they require a modeling approach that reflects the complexities and nonlinearity of the environment. Bradford et al. (2016) suggest “model-knowledge integration” where models can be accurately represented by adding our advanced knowledge of carbon stabilization to improve feedback projections. Moving forward we need to bring together theory, measurement and modeling in order to predict accurate relationships and create sustainable management decisions.

Further in-depth resources

Steefel et al., (2005) doi ; Bradford et al., (2016) doi ; Lehmann and Kleber (2015) doi ; Schmidt et al. (2011) doi

Building global scale observations and experimental datasets

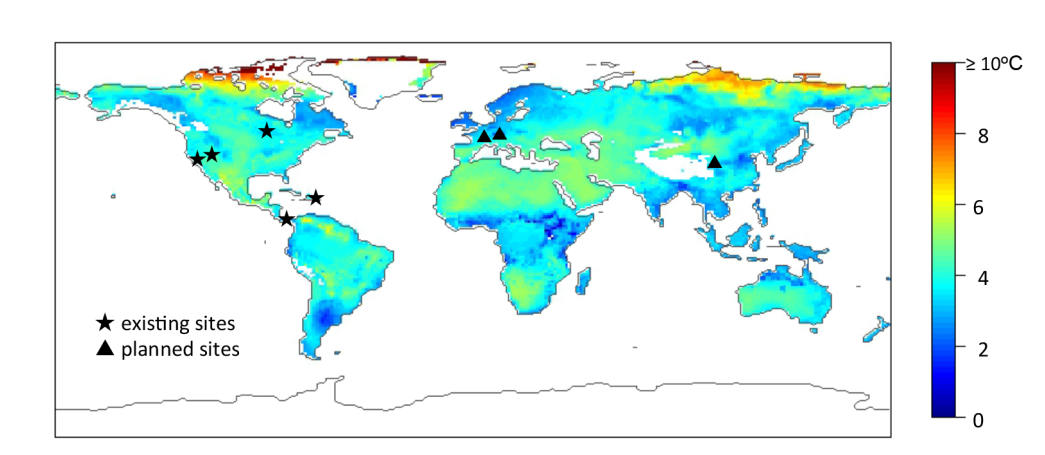

With a push towards more mechanistic representations of SOC cycling in ESMs, there is an urgent need to compile enhance global datasets for model development and validation. The International Soil Carbon Network (ICSN) is a “large-scale synthesis of soil carbon science” ISCN. This network synthesizes data about soil carbon into a single platform that then can be used to understand some of the still under answered questions on soil carbon dynamics. One of the largest questions is carbon stabilization and destabilization and under what conditions do either exist, which is critical in the face of climate change. Mostly soil carbon experiments focus solely on the top 30 cm of soil and the relationship of climate change to deep soil carbon is still widely unexplored. The is what created the call for the International Soil Experimental Network (ISEN). ISEN is a global database of manipulative soil warming experiments that focus specifically on the effects of warming deep (at least to 1m) soil profiles (Torn et al. 2015). Networks like the ISCN and ISEN provide the framework for the addition of data into a global soil carbon database. This data can then be used to extrapolate global soil carbon stocks and how they may change in the future due to climate change. This kind of data is an important step in reducing uncertainty in ESMs.

Figure 8: Existing and planned sites for the ISEN at the time of the paper publication. The global temperature map shows the predicted increase in mean temperature for 2080-2100 at 0.01 m soil depth (Torn et al. 2015)

Figure 8: Existing and planned sites for the ISEN at the time of the paper publication. The global temperature map shows the predicted increase in mean temperature for 2080-2100 at 0.01 m soil depth (Torn et al. 2015)